Typesetting Poems with LaTeX📄📄📄

First published on .

There are not many options when trying to typeset a collection of poetry. A word processor provides the necessary functionality, but it is not well suited for the work. Adobe’s InDesign provides the necessary precision but at a high cost, especially for smaller teams or individuals attempting to compile poems without paying Adobe’s monthly fees. For those who are looking for alternatives, LaTeX provides both a precise and free alternative.

What is LaTeX?

LaTeX is a typesetting software, originally developed in 1983 for academic writing. Unlike other document preparation software, LaTeX is not a WYSIWYG (what you see is what you get), but instead uses a markup-like syntax to describe the document.

What that means in practice is that a LaTeX document reads much like an HTML document, with commands outlining different elements of the document.

Getting Started with LaTeX

In order to start compiling your poems with LaTeX you will need

1. To Install LaTeX

I recommend that you use TeX Live. The TeX User Group website provides installations and instructions for Windows, MacOS, and Linux. There are other free distributions of LaTeX; however, TeX Live is the most compatible with my text editor of choice.

2. A Text Editor

You can use whatever text editor you’re most comfortable with to compose your document; however, I recommend Microsoft’s Visual Studio Code (Available on all platforms) since it integrates with LaTeX using the LaTeX Workshop Extension and allows you to compose and preview the output of your LaTeX in the same window.

(For more information on installing and managing extensions on VS Code check out this link)

Alternatively you can also use OverLeaf to edit your LaTeX documents. You will need to create an account, but once you do you can immediately start editing your document from your browser without installing anything!

3. Learn the Basics of LaTeX syntax

LaTeX has existed since 1983, so there are plenty of resources that you can use to learn the basics of LaTeX, but here’s a short introduction to get you started.

The Basics of LaTeX

- All commands in LaTeX begin with a backslash (

\) and often include arguments contained in curly brackets ({}). - Every LaTeX document begins with a

\documentclasscommand. The\documentclasscommand uses different arguments depending on the type of document you wish to produce. - Another type of command syntax can be seen with the

\begin{document}and\end{document}commands. These commands bookend the content of a LaTeX document much like the content of an HTML document is found between the<body>and</body>tags. You will see that other commands use the same\begin{}and\end{}structure to define different elements of the document. - Comments in LaTeX are defined by the

%character. Any text on the line following the character will be ignored by the LaTeX compiler. - Some times you will need functionality that is not supported natively by LaTeX. In these cases you can take advantage of packages that are included with your LaTeX distribution. In order to use these packages simply include the

\usepackage{package-name}command at the beginning of your document. LaTeX includes a large variety of packages which extend its functionality allowing you to manage page margins, change fonts, print mathematical formulas, or even typeset critical editions of poetry.

Keeping all that in mind, here is the minimum starting point to create a LaTeX document:

\documentclass{article}

\begin{document}

%The text of the document will go here.

\end{document}Typesetting a Poem with poemscol

Now that we have some background, we can return to the original problem - typesetting a collection of poetry. To typeset poetry with LaTeX we’re going to take advantage of one of LaTeX’s existing packages - poemscol. Poemscol was originally developed to typeset critical editions of poetry so it has more than enough functionality for what we’re trying to do.

Before we can use the package we have to import it by adding these two commands to the top of our document \usepackage{poemscol} and \usepackage{fancyhdr}. Fancyhdr is another LaTeX package required by poemscol, so we will have to include it every time we create a poemscol document. Once we’ve done that we’re ready to start typesetting a poem!

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{fancyhdr} % required by poemscol

\usepackage{poemscol} % required to typeset poems

\begin{document}

%The text of the document will go here.

\end{document}The Poem Command

Now that we’ve imported the package, it’s time to use the poem command to declare our poem. Much as we used the \begin{document} and \end{document} commands to begin and end our document, we will use the \begin{poem} and \end{poem} commands to define the beginning and end of our poem.

\documentclass{article}

\usepackage{fancyhdr} % required by poemscol

\usepackage{poemscol} % required to typeset poems

\begin{document}

\begin{poem}

%The text of the poem will go here.

\end{poem}

\end{document}To add a title, just place the command \poemtitle{Title} before the beginning of the poem, and all that we’re missing is the poem.

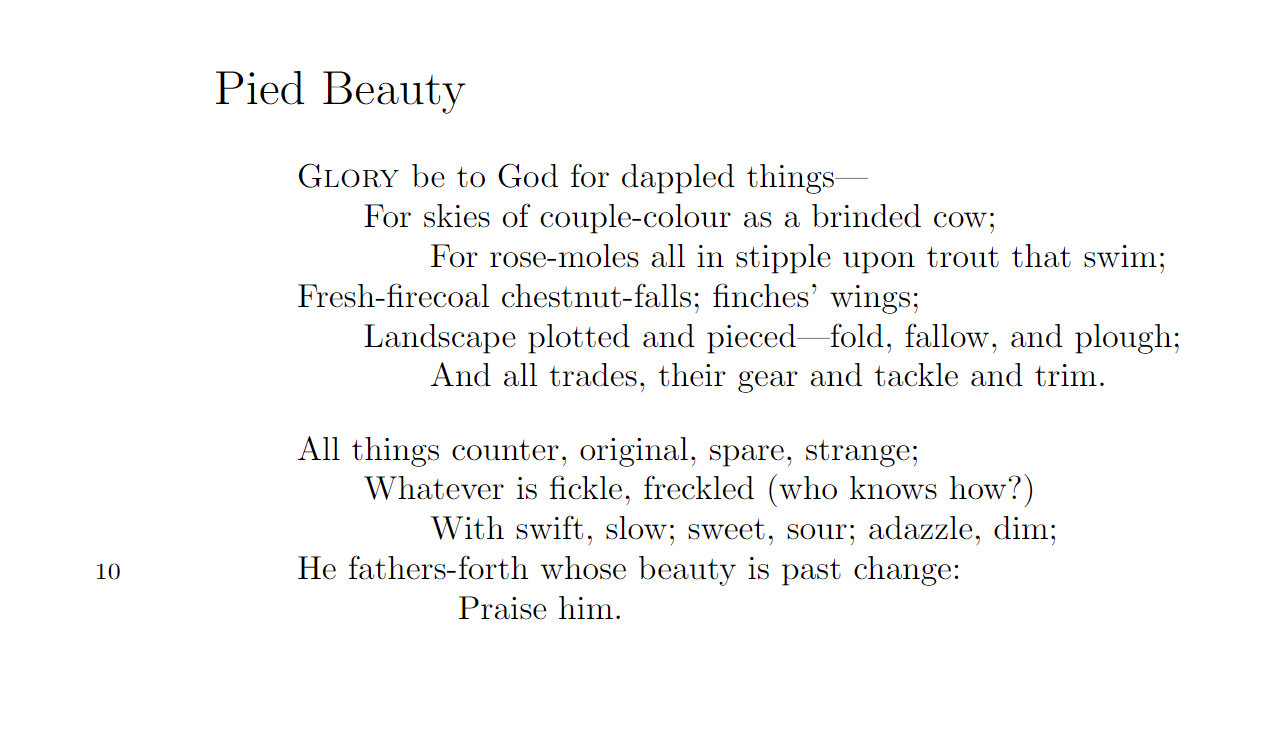

For this example, I’m going to use Gerard Manley Hopkin’s poem Pied Beauty since it allows us to demonstrate two staples of typesetting poetry - stanzas and indented lines.

Lines, Stanzas, and Indents

Stanzas function just like the poem and document commands we used earlier. To begin a stanza issue the \begin{stanza} and \end{stanza} to end the stanza.

However, marking out the stanzas is not enough, we also have to define each line of verse. Because LaTeX is not a word processor, it does not interpret a line break in the source code as a line break in the final document. For this reason every line (except for the last one of a stanza) must end with the \verseline command to indicate the end of a line of verse.

Poets will also occasionally use indentation to set lines apart. In poemscol indents are issued in-line by using the command \verseindent.

After copying in the poem and using these commands our typeset document should look something like this:

\poemtitle{Pied Beauty}

\begin{poem}

\begin{stanza}

G\textsc{lory} be to God for dappled things--- \verseline

\verseindent For skies of couple-colour as a brinded cow; \verseline

\verseindent\verseindent For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim;\verseline

Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches’ wings;\verseline

\verseindent Landscape plotted and pieced—fold, fallow, and plough;\verseline

\verseindent\verseindent And all trades, their gear and tackle and trim.\verseline

\end{stanza}

\begin{stanza}

All things counter, original, spare, strange;\verseline

\verseindent Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?)\verseline

\verseindent\verseindent With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim;\verseline

He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change:\verseline

\versephantom{He fathers-}Praise him.

\end{stanza}

\end{poem}You may have noticed a couple commands I haven’t explained yet. Let’s start with \versephantom{}. Versephantom is useful when you want to customize the size of your line indent. The verseindent command can be redefined, but that would affect all instances of the command. Versephantom allows you to create an indent of any character size - in this case Hopkins indented the final line so that its first letter falls on the first letter of the word forth on the line above. By issuing the command with an argument of “He fathers-” we are telling LaTeX to create whitespace equal to the length of the phrase “He fathers-”, which allows us to indent exactly as Hopkins did.

The other command you may have noticed is \textsc{}. This is an example of how you format text in latex. \textsc indicates that the text should be printed in small caps, \textit indicates that the text should be italicized, and \textbf indicates that the text should be bolded.

Once you’ve finished entering these commands the finished document should look similar to this:

And just like that you’ve typeset your first poem using LaTeX!

Other things to read

- Which Poetic Form is Best?How to choose which form to use to write a poem.

- Son of CainThoughts on Steinbeck's East of Eden and a poem inspired by the story of Cain and Abel.

- On Writing Poems DailyMy reflections on writing one poem every day for a year.